Kathy Vu, BScPhm, PharmD, ACPR

Clinical Lead, Safety Initiatives, Cancer Care Ontario

Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream and Director, PharmD for Pharmacists Program, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto

Leta Forbes, MD, FRCP(C)

Provincial Head, Systemic Treatment, Cancer Care Ontario

Medical Oncologist, R.S. McLaughlin Durham Regional Cancer Centre, Lakeridge Health

Daniela Gallo-Hershberg, BScPhm, PharmD

Group Manager, Systemic Treatment Program, Cancer Care Ontario

Assistant Professor (Status only), Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto

Sarah Salama, BScPhm, PharmD

Systemic Treatment Pharmacist, Systemic Treatment Program, Cancer Care Ontario

INTRODUCTION

Emily is a 44-year-old patient known to your pharmacy. She has two young children and often seeks advice from the pharmacists at the pharmacy when her kids are unwell. Today she comes in alone and tells you that she was recently diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. She is coping well with the news and is thankful that the cancer has not spread to other organs in her body. She will be starting chemotherapy next week. She proceeds to hand you information sheets and prescriptions given to her by the oncology team. Based on the information provided, she will be started on a chemotherapy regimen called dose-dense AC (doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide)-Paclitaxel (AC-T) and trastuzumab for eight treatment cycles. Her prescriptions for the first component of her chemotherapy, AC, consists of:

- Olanzapine 5 mg PO daily on days 1 – 4

- NEPA (palonosetron 0.5 mg PO and netupitant 300 mg PO) x 1 on day 1

- Dexamethasone 8 mg PO daily on days 2 – 4

- Prochlorperazine 10 mg PO q4-6h PRN nausea/vomiting

Emily was told to fill the prescriptions and bring them to clinic on the day of chemotherapy. She believes that they are for nausea and vomiting but she is surprised there are so many different medications on the prescription. She will meet with the pharmacist at the oncology clinic next week. She is hoping you could help explain these medications to her, including how to take them.

This scenario may be familiar to those who provide care to patients with cancer. However, the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) has changed substantially in the past year in Ontario so the medications may be unfamiliar to even those who are experienced in the management of CINV.

This article will review the new Cancer Care Ontario Antiemetic Guideline released in 2019 and discuss the implications to clinical practice.

BACKGROUND

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains a feared side effect of cancer treatment for many patients. Despite the tremendous advances in the management of CINV over the past decade, prevention remains suboptimal and presents a clinical challenge to healthcare providers and patients undergoing cancer treatment.

The pathophysiology of CINV is complex and involves many receptors and neurotransmitters. The main targets for treatment involve 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT3) and its receptors, substance P and the neurokinin-1 receptors, and dopamine and its receptors (See Table 1). In addition to these well-studied neurotransmitters, other mechanisms also contribute to management of CINV as demonstrated by the effects of medications such as dexamethasone or lorazepam.

CINV can occur in three distinct phases following a dose of chemotherapy: The Acute phase of CINV occurs within the first 24 hours after chemotherapy administration. Delayed CINV generally occurs after the 24-hour mark but there may be some overlap with the acute phase. Breakthrough CINV can occur at any time during the acute and delayed phase despite prophylaxis. We expect some degree of breakthrough CINV and it is considered mild if treated with one to two doses of rescue medication. Additionally, patients may also experience anticipatory nausea and vomiting. This occurs when patients experience suboptimal control of emesis or nausea in a previous cycle. Anticipatory CINV is thought to be a conditioned response as opposed to a physiologic response to chemotherapy since the symptoms occur before chemotherapy is administered. For example, patients with anticipatory CINV will complain of emesis while waiting to receive cancer treatment.

Table 1: Common neurotransmitters and receptors responsible for CINV

MANAGEMENT OF CHEMOTHERAPY-INDUCED NAUSEA AND VOMITING

The management of CINV focuses on preventative strategies to control and minimize the incidence of nausea and vomiting. The optimal antiemetic regimen will be tailored to the emetic potential of the regimen as well as individual patient factors. The regimen may include multiple medications to ensure that all phases and associated neurotransmitters are adequately addressed. Therefore, the optimal regimen may consist of three to five medications aimed at acute, delayed and breakthrough CINV.

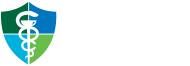

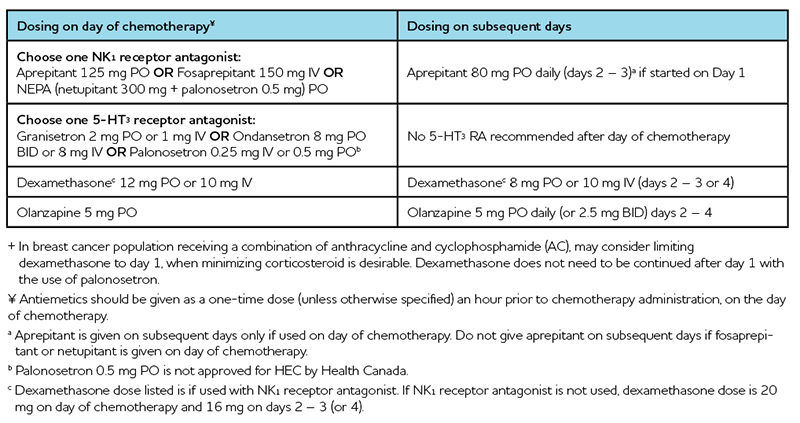

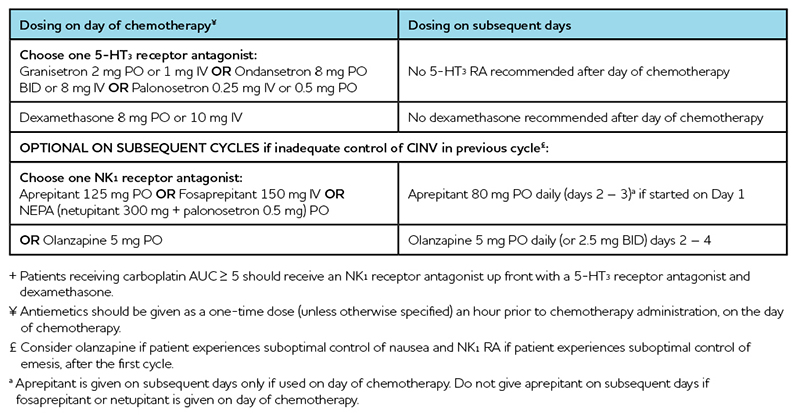

The 2019 Antiemetic Recommendations for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Clinical Practice Guideline1 provides guidance for the prevention of highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC), moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC), low emetogenic chemotherapy and minimally emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. In addition, there are recommendations for the management of multiday intravenous chemotherapy as well as oral chemotherapy. A review of the literature was also conducted to gather evidence for the role of cannabinoids and medicinal cannabis in the management of CINV. Tables 2 to 6 summarize the recommendations for the management of CINV from the Cancer Care Ontario Antiemetic Clinical Practice Guideline.

Table 2: Management of Highly Emetic Single-Day Intravenous Chemotherapy1

Table 3: Management of Moderately Emetic Single-Day Intravenous Chemotherapy1

Table 4: Management of Low Emetic Single-Day Intravenous Chemotherapy1

Table 5: Management of Minimally Emetic Single-Day Intravenous Chemotherapy1

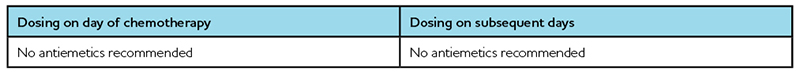

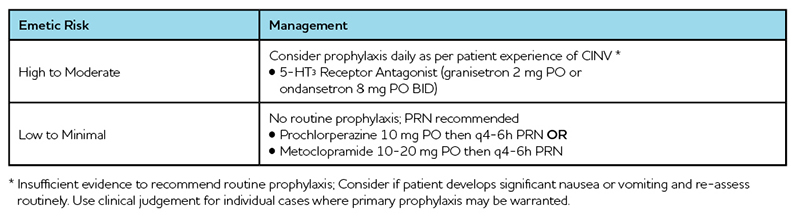

Table 6: Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Oral Anticancer Medications1

The management of CINV with oral anticancer medications takes a slightly different approach than with intravenous chemotherapy. Since patients usually take oral anticancer medications daily for weeks at a time, there is the potential for tolerance to nausea and vomiting and unnecessary side effects (e.g. constipation with indefinite daily 5-HT3 receptor antagonists) to occur. Thus, the approach is to consider providing routine antiemetic prophylaxis for HEC and MEC oral agents and only as needed for low and minimal emetic risk oral agents. If routine prophylaxis is initiated, CINV should be assessed routinely (e.g. weekly) to determine if ongoing routine treatment is required. This approach differs from international guidelines where a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist (5-HT3 RA) is recommended to all patients taking a HEC or MEC oral agent.

Cannabinoids in the Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Due to the lack of high quality clinical trials, no recommendation can be made to incorporate synthetic or non-synthetic cannabinoids as part of standard antiemetic therapy. If a cannabinoid is used, it should be after optimal therapy (including combination therapy with a 5-HT3 RA, NK1 RA, dexamethasone and olanzapine) has failed to provide adequate control of nausea and vomiting. Patients may ask for advice on the use of cannabis and in these cases, they should be guided to seek advice from a health care professional familiar with cannabis and use products with consistent concentrations from a reputable source.

Back to our patient, Emily…

Emily will be starting systemic treatment with AC-T given in a dose-dense manner for her high risk, early stage breast cancer. A number of resources can be used to determine the emetic risk of a chemotherapy regimen. Cancer Care Ontario’s Drug Formulary website is a good resource as it is Ontario-specific. The British Columbia Cancer Agency also has a Drug Information website that provides information on systemic treatment regimens, supportive care as well as patient information resources. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Society of Clinical Oncology also provide information on the risk of emesis for cancer drug therapies.

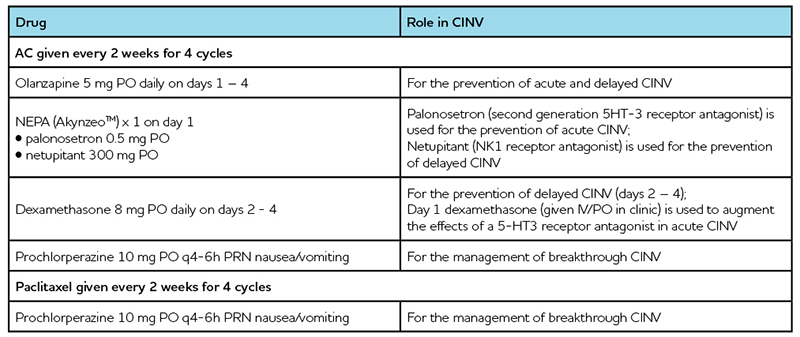

With respect to the AC-T chemotherapy regimen, the Cancer Care Ontario Drug Formulary designates AC regimens as high emetic risk while paclitaxel (Taxol) is designated as low emetic risk. Let us look at the prescriptions provided (Table 7) to see if the antiemetic regimen is appropriate for her AC-T regimen.

Table 7: Emily’s Antiemetic Regimen

The uptake of the antiemetic recommendations may take some time to see in clinical practice. In June 2019, NEPA (palonosetron and netupitant) was listed on the Ontario Drug Benefit program. The use of this combination product is likely to increase as it offers the convenience of two medications in one capsule, thereby reducing the pill burden. Olanzapine is associated with significant sedation and may increase the risk of falls, especially in elderly patients and those taking other medications that are associated with sedation. Despite the sedation, multiple studies have demonstrated olanzapines efficacy in HEC and MEC regimens, particularly when nausea is uncontrolled.2-5

Based on Emily’s prescriptions, she is on the most appropriate antiemetic regimen for her AC-T chemotherapy regimen. However, we must ensure that she understands how to take her antiemetic mediations appropriately (adherence) and to monitor her for uncontrolled CINV in the next two to three days after her first cycle. It is also important that she understands the side effects she may experience with the medications and when she may want to contact her oncology team to discuss uncontrolled symptoms.

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

Practice varies between oncology day clinics across the province and the country. In Ontario, some chemotherapy day clinics may provide the pre-chemotherapy antiemetics including dexamethasone, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and NK1 receptor antagonist (rarely) intravenously. Sometimes they provide them via oral route in the clinic. In other clinics, they give patients a prescription for all three medications to use before treatment.

Drug Access Facilitators are relatively new roles in many cancer centers. They help patients explore their eligibility for financial and compassionate access to available drug programs (e.g. Trillium program, compassionate programs through pharmaceutical companies). If a patient experiences financial burden, advise them to speak with their Drug Access Facilitator, if available, at their cancer center.

REFERENCES:

- Cancer Care Ontario. The 2019 Antiemetic Recommendations for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/content/2019-antiemetic-recommendations-chemotherapy-induced-nausea-and-vomiting-clinical-practice-guideline.

- Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, Liu H, Powell SF, Bajaj M, Dietrich L, Biggs D, Lafky JM, Loprinzi CL. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):134.

- Chiu L, Chow R, Popovic M, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine for the prophylaxis and rescue of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2381-2392. doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3075-8.

- Yanai T, Iwasa S, Hashimoto H, et al. A double-blind randomized phase II dose-finding study of olanzapine 10 mg or 5 mg for the prophylaxis of emesis induced by highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(2):382-388. doi:10.1007/s10147-017-1200-4.

- Sato J, Kashiwaba M, Komatsu H, Ishida K, Nihei S, Kudo K. Effect of olanzapine for breast cancer patients resistant to triplet antiemetic therapy with nausea due to anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(5):415-420. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyw011