Lesley Graham1,2

Sylvia Hyland3

Beth Sproule1,2,4

1 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario.

2 Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

3 Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Toronto, Canada.

4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

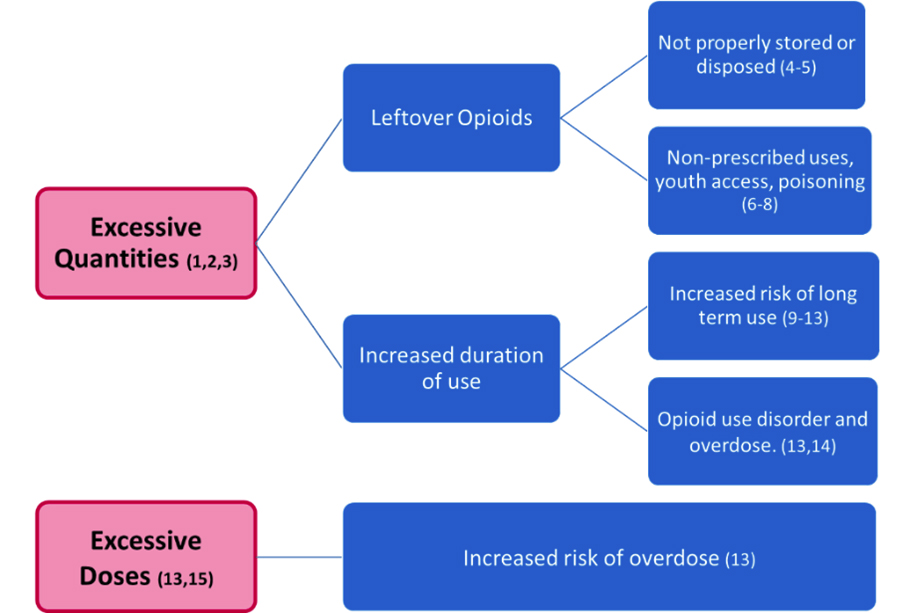

Many assume that the short-term use of opioids for acute pain is reasonable and safe. Opioid stewardship activities have primarily focused on opioid use for chronic pain, however recent research has provided a robust evidence-base on the balance between benefits and harms of opioid use for acute pain. We now know that patients are receiving excessive quantities and doses of opioids for acute pain that can lead to harm (See Figure). Improving the safety of prescribed opioids continues to be an important harm prevention measure, especially in the context of the current opioid crisis.

Figure: Harms associated with excessive opioid quantities and doses for acute pain.

What do you think of the following prescriptions?

Rx 1

- 30 x acetaminophen 325mg / oxycodone 5mg tablets with directions to take one to two tablets every four to six hours when required for pain

- Patient: 16-year-old male, opioid naive, who has just undergone a routine wisdom tooth extraction.

Rx 2

- 60 x oxycodone 5mg tablets with directions to take one to two tablets every four to six hours when required for pain

- Patient: 53-year-old male, opioid naive, who has just undergone a cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal).

When reflecting on these prescriptions, here are key points to consider:

- Quantities of up to 20 tablets are sufficient for most indications (with the exception of a few major surgical procedures, see Best Practice in Surgery Guidelines (16))

- Maximum daily doses should not exceed 50 mg morphine equivalents (MME) in opioid naïve patients (17)

- Opioids are not indicated for pain after routine wisdom tooth extractions, unless alternatives are contraindicated or inadequate (however this is unlikely) (18, 19)

- Opioids are indicated if required for severe acute pain when alternatives are either inadequate or contraindicated (16)

Pharmacists are ideally placed to have a significant role to mitigate patient harm as they have the authority to dispense smaller quantities of medications including opioids (20) and can advise on safer daily doses of opioids. A series of eLearning modules and resources, based on the Health Quality Ontario (HQO) Standard for Opioids in Acute Pain (17), were developed to support pharmacists in this role. (Box 1)

Box 1: Opioids for Acute Pain – Roles for Pharmacists (17)

Assess prescriptions considering:

- the treatment plan should include non-opioid pharmacotherapy, with opioids added only when appropriate.

- the dose should be the lowest effective opioid dose (< 50 MME per day for opioid naïve patients) of the least potent immediate-release product

- a duration of 3 days or less is often sufficient (more than 7 days rarely indicated)

Always counsel patients on:

- the potential benefits and harms of opioid therapy

- safe storage and disposal. Discourage the practice of keeping opioids for a rainy day!

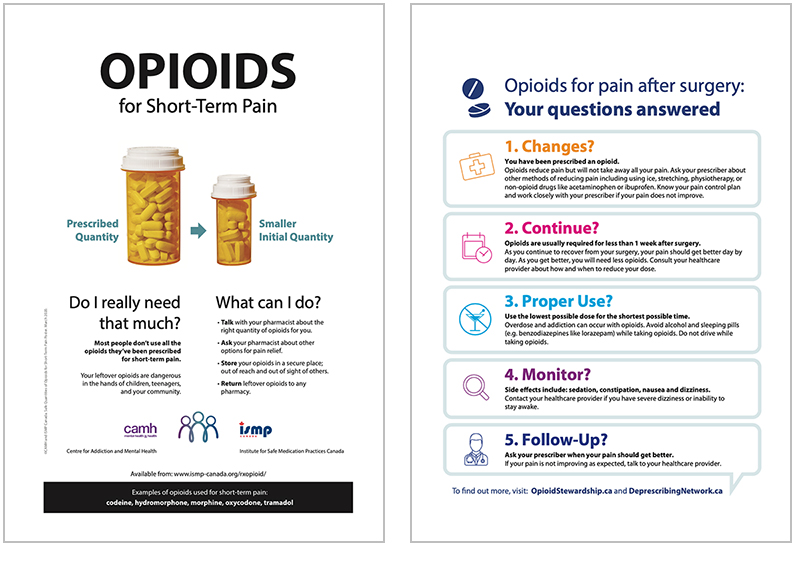

The eLearning modules show how to apply this knowledge in practice using case studies, example questions and a demonstration of the language that could be used to suggest a smaller quantity, hold an opioid prescription or manage challenging questions from patients. Resources to support pharmacists in implementing these recommendations in a busy pharmacy include: a quick reference guidance document on choosing an appropriate quantity; the calculated number of tablets per day of opioid medications to stay within 50 MME; and a handout and poster for patients. The modules (Box 2) and resources were tested by community pharmacists and patients in Ontario during the development process and are freely available at the ISMP Opioids in Acute Pain website: https://www.ismp-canada.org/rxopioid/

Box 2: eLearning Modules Series

The eLearning series consists of 5 modules – each approximately 15 to 20 minutes long.

- Opioids for Acute Pain: Is there a problem? Covers the problems associated with the well-intentioned, but excessive prescribing of opioids in acute pain.

- Your Role in Safe Opioid Use for Acute Pain. Refers to the Health Quality Ontario provincial standard on opioid use in acute pain, and how you can use this to improve safety.

- Appropriate Opioid Quantities in Acute Pain. Helps translate recommended durations of use into appropriate quantities of opioids for acute pain.

- Tips for Productive Patient Discussions. Describes phrases that you can use when discussing difficult topics with patients such as suggesting smaller quantities of opioids.

- Everyday Practice: How to make this work in your pharmacy. Shows you how you could implement opioid stewardship activities into your practice.

This educational program was evaluated by surveying pharmacists in Ontario (n=182). Findings included:

- 94% of pharmacists reported that they gained knowledge and skills that were meaningful to their practice

- 85% reported that they would be able to apply what they had learned in practice.

- The percentage of pharmacists who knew the maximum daily dose of opioids increased from 56% to 100% before and after engaging with the modules (p < 0.001)

- The percentage of pharmacists who could recognize excessive quantities of opioids increased from 78% to 98% before and after engaging with the modules (p < 0.002)

- 90% of participants felt that it was their role to promote the safer use of opioids in acute pain

- Pharmacists who intended to offer part-fills increased from 26% in the pre-module group to 74% in the post-module group (p<0.001)

There is evidence linking the initiation of the opioid crisis to the increased availability of opioids over the course of the 2000s due to well-intentioned over-prescribing of opioids for chronic pain. (21) Opioid stewardship prevention measures complement the important treatment (e.g., opioid agonist therapy) and harm reduction initiatives (e.g., safer opioid supply programs) that also require pharmacist involvement to address the crisis.

Pharmacists are well positioned to help make opioid prescribing for acute pain safer, particularly as they serve as central points to partner with patients who may receive care from a range of prescribers. They also have the knowledge, skills and judgement to complete medication‐related therapeutic assessments and can make recommendations to patients regarding appropriate quantities and doses for initial opioid prescriptions for acute pain. Of note, OCP’s Opioid Policy (22) states that pharmacy practice should be in alignment with provincial and federal opioid strategies, including the HQO standards (17). Additionally, one of OCPs Quality Indicators is the percentage of patients who were newly dispensed an opioid prescription greater than 50 mg MME per day. (23) The eLearning modules and resources now available were designed to help support these best practices.

Free Access to Modules and Resources

Please go to https://www.ismp-canada.org/rxopioid/ to access modules and many resources (including a handout and poster for patients).

Funding provided by the Substance Use and Addictions Program, Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

References

- Bicket M, Long J, Pronovost P et al. Prescription Opioid Analgesics Commonly Unused After Surgery. A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066-1071.

- Daoust R, Paquet J, Cournoyer A et al. Quantity of opioids consumed following an emergency department visit for acute pain: a Canadian prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022649. Doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022649.

- Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, et al. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016; 168:328-334.

- Bartels, K., Mayes, L. M., Dingmann, C., Bullard, K. J., Hopfer, C. J., & Binswanger, I. A. (2016). Opioid Use and Storage Patterns by Patients after Hospital Discharge following Surgery. PloS One, 11(1), e0147972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147972

- Gregorian, R., Marrett, E., Sivathanu, V., Torgal, M., Shah, S., Kwong, W. J., & Gudin, J. (2020). Safe Opioid Storage and Disposal: A Survey of Patient Beliefs and Practices. Journal of Pain Research, 13, 987–995. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S242825

- McCabe S, West B, Boyd C. Leftover prescription opioids and non- medical use among high school seniors: A multi-cohort national study. J Adolescent Health. 2013:52(4):480-485.

- Boak, A., Elton-Marshall, T., & Hamilton, H. A. (2022). The well-being of Ontario students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/en/science-and-research/institutes-and-centres/institute-for-mental-health-policy-research/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey—osduhs

- Finkelstein, Y., Macdonald, E. M., Gonzalez, A., Sivilotti, M. L. A., Mamdani, M. M., Juurlink, D. N., & Canadian Drug Safety And Effectiveness Research Network (CDSERN). (2017). Overdose Risk in Young Children of Women Prescribed Opioids. Pediatrics, 139(3), e20162887. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2887

- Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use – United States, 2006-2015. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. 2017; 66(10):265-9: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6610a1.htm.

- Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H et al. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery; a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:425-430.

- Neuman M, Bateman B, Wunsch H. Inappropriate opioid prescriptions after surgery. Lancet. 2019; 393:1547-57.

- Arwi, G. A., & Schug, S. A. (2020). Potential for Harm Associated with Discharge Opioids After Hospital Stay: A Systematic Review. Drugs, 80(6), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01294-z

- Gomes, T., Campbell, T., Tadrous, M., Mamdani, M. M., Paterson, J. M., & Juurlink, D. N. (2021). Initial opioid prescription patterns and the risk of ongoing use and adverse outcomes. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 30(3), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5180

- Brat, G. A., Agniel, D., Beam, A., Yorkgitis, B., Bicket, M., Homer, M., Fox, K. P., Knecht, D. B., McMahill-Walraven, C. N., Palmer, N., & Kohane, I. (2018). Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 360, j5790. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5790

- Pasricha, S. V., Tadrous, M., Khuu, W., Juurlink, D. N., Mamdani, M. M., Paterson, J. M., & Gomes, T. (2018). Clinical indications associated with opioid initiation for pain management in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study. PAIN, 159(8), 1562–1568. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001242

- Best Practice in Surgery Guidelines – Prescription of Pain Medication at Discharge after Elective Surgery. http://bestpracticeinsurgery.ca/guidelines/painmed/

- Health Quality Ontario (HQO) – Quality Standard on Opioid Prescribing for Acute Pain, 2018. https://www.hqontario.ca/Evidence-to-Improve-Care/Quality-Standards/View-all-Quality-Standards/Opioid-Prescribing-for-Acute-Pain

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario Guidelines – The Role of Opioids in the Management of Acute and Chronic Pain in Dental Practice, 2015. https://az184419.vo.msecnd.net/rcdso/pdf/guidelines/RCDSO_Guidelines_Role_of_Opioids.pdf

- Moore P, Ziegler K, Lipman R et al. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain: An overview systematic reviews. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2018;149(4):256-265.

- Ontario College of Pharmacists – Fact Sheet: Prescription Refills, Part-Fills and Intervals. https://www.ocpinfo.com/practice-education/practice-tools/fact-sheets/prescription-refills-part-fills-and-intervals/?hilite=part-fill.

- National Advisory Committee on Prescription Drug Misuse. (2013). First do no harm: Responding to Canada’s prescription drug crisis. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. https://www.ccsa.ca/first-do-no-harm-responding-canadas-prescription-drug-crisis-report

- Ontario College of Pharmacists – Opioid Policy, 2018. https://www.ocpinfo.com/regulations-standards/practice-policies-guidelines/opioid-policy/

- Ontario College of Pharmacists – Quality Indicators Tool Kit. 2020. https://www.ocpinfo.com/practice-education/quality-improvement-data-for-pharmacy/quality-indicators-data-resources/