Adrian Boucher, RPh, BSc, PharmD 1,2

Certina Ho, RPh, BScPhm, MISt, MEd, PhD 1,2

1 Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada

2 Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto

In clinically complex healthcare settings, adverse events and medication errors can occur despite the best intentions of healthcare professionals. Healthcare organizations typically take a structured approach to providing care and supporting patients and their families when an unintended event results in patient harm. However, healthcare practitioners involved in a critical incident can also experience emotional trauma, from sadness and concern to suffering and anguish, which often go unrecognized and overlooked.1

A PHARMACIST’S STORY

The following pharmacist’s story is extracted from the October 31st, 2017 issue of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada ISMP Canada Safety Bulletin “The Second Victim: Sharing the Journey toward Healing”:2

“About two years ago, while transcribing an order, I made a single incorrect keystroke on my keyboard, and a patient’s anticoagulant was held instead of being restarted. The patient went on to develop an extensive arterial thrombus that eventually led to her death.

The first few days after the patient died, honestly, were terrible. I was flooded with thoughts and emotions that I could hardly even identify at the time. I felt incredibly sad. I was anxious. I was scared of being sued. I felt alone. I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t able to use my thinking to take control of my emotions. I wasn’t sure what to say or do. Others tried to say helpful things, but no words helped, especially words that tried to convince me I shouldn’t feel so bad.”

It is estimated that almost 50 per cent of healthcare providers will experience a medical error or unintentional adverse event that results in significant mental distress at least once in their career.3 Frequently, these practitioners feel personally responsible for the unexpected patient outcomes, leading them to second-guess their clinical skills and knowledge base.4

Following an incident, practitioners will often experience symptoms that include extreme sadness, difficulty concentrating, depression, repetitive and intrusive memories, and sleep disturbances, which can result in absenteeism and a reduced ability to perform at work (Figure 1).5 For most, these symptoms pass with time, but for a few, the effects can be long lasting.6

Aftermath of a Medical/Medication Incident

Common Symptoms Experienced by Healthcare Practitioners

- Extreme sadness

- Difficulty concentrating

- Depression

- Repetitive and intrusive memories

- Sleep disturbances

- Avoidance of similar types of patient care

Figure 1. Symptoms Reported by Healthcare Practitioners Involved in Patient Safety Investigations5

Not everyone involved in a patient safety incident will experience emotional trauma, but there are a number of factors that may influence the impact of an incident on a practitioner. Incidents associated with harm or death, patients who “connected” the clinician to his/her own family (such as a patient with the same name, age, or physical characteristics as a loved one), the length of relationship between the patient and the practitioner, and the involvement of pediatric patients, can all contribute to the overall impact of an event.6 In addition, certain aspects of the healthcare organization’s environment, such as its safety culture, may protect against or intensify incident-related trauma.4

THE RECOVERY PROCESS

“Some days I could breathe through the emotion, some days I completely fell apart and had to go home. I wasn’t sure I should be working, but I worried that if I went home for too long, I might never come back to work again. I got offered the hospital’s employee assistance program. I declined. In the first few days, everything felt scary in ways that made no sense. I knew I should probably be talking to someone, but I was scared to, and I didn’t know why. And so, I sought out my own help. I connected with a trusted colleague who had experienced something similar, and that helped me feel less alone. I connected with a friend in pastoral care, and we just sat together. I did some art in the hopes of processing parts of the experience.”2

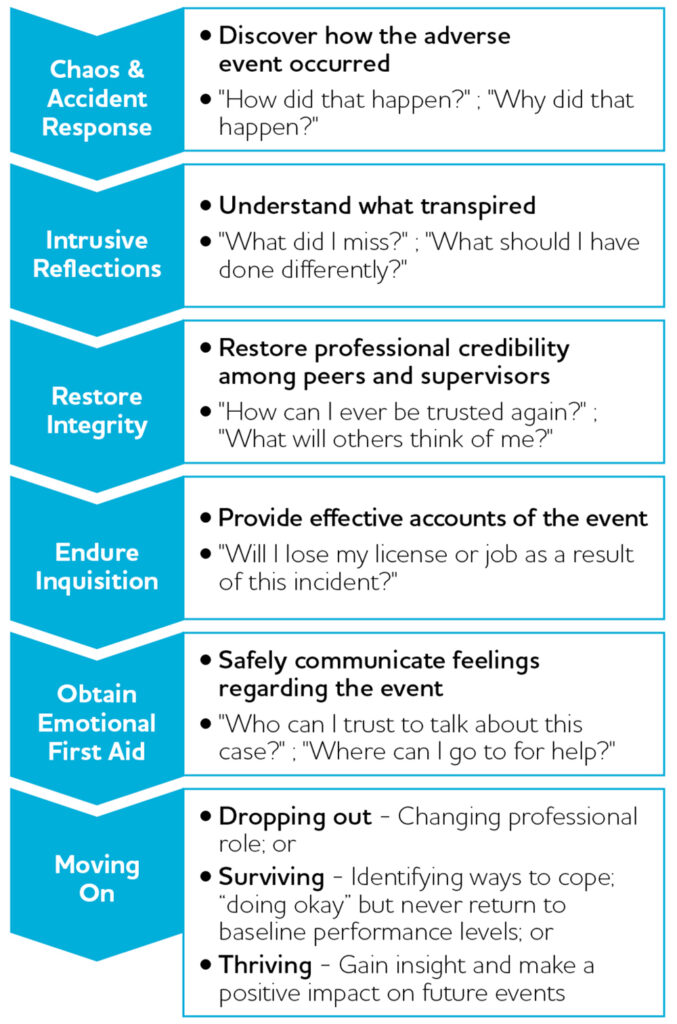

The personal recovery process following an incident typically involves six steps: (1) chaos and accident response; (2) intrusive reflections; (3) restore integrity; (4) endure inquisition; (5) obtain emotional first aid; and (6) moving on (Figure 2).6 Practitioners who have successfully navigated this process highlight specific interventions that can aid recovery.6 One is simply discussing the incident with peers and colleagues, especially those who have previously been involved in an incident.7

Sharing stories with a supportive colleague who is not judgmental can give the practitioner insight and reassurance and help reduce feelings of isolation. This can be a powerful support mechanism and appears to be preferred to external services (e.g. mental health professionals) following an event.

Another coping strategy is for practitioners to participate in the case review (e.g. root cause analysis or comprehensive analysis) to help address identified system issues and build action plans to prevent future incidents. Inclusion in these blame-free discussions helps promote clinician healing and recovery. Finally, practitioners can participate in disclosure. Patients and families can be surprisingly forgiving when the error is disclosed by a caring practitioner with a sincere apology.1

Figure 2. Trajectory of the Recovery Process6

Organizations can also support the recovery process, for example, through employee assistance programs. A number of institutions have demonstrated success and cost-effectiveness of peer-to-peer support hotlines for those who experienced trauma.8,9

Like any program that involves disclosing sensitive information, there are a number of barriers to access, including stigma associated with reaching out for help, fear of losing professional respect, fear of losing income, perception that using a program indicates weakness, not feeling like one’s problems are important, difficulty taking time off work, and doubts about confidentiality of services offered.9 As such, it is important that organizations aim to create a culture of safety, where employees are supported and encouraged to discuss errors openly, and contribute to organizational change.

A perceived low level of organizational support has been linked to negative outcomes, such as ongoing emotional distress, intention to leave employment, and absenteeism. A supportive and fair culture that facilitates discussion and sharing, promotes reporting of incidents and near misses, and creates opportunities for learning has been associated with the avoidance of these negative outcomes.5

SUMMARY

Despite our best efforts, healthcare practitioners are not perfect, and mistakes do happen. The above pharmacist’s story highlights the challenges practitioners may experience following a critical incident and the lessons learned through the recovery process. The healthcare organization, colleagues, and those involved can all play a role in facilitating the recovery process of the affected individuals (Figure 3).

Organizations can nurture a workplace culture in which practitioners are not afraid to seek help and establish or strengthen practitioner support programs. Colleagues, especially those who have gone through similar experiences, can play the vital role of peer support. Practitioners can take part in the disclosure process, work with the patient, the family, and the organization to identify solutions to prevent future incidents.

| Healthcare Practitioners | Organizations |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 3. Facilitating the Recovery Process

Caring for the patient and the family is always the priority following a medication incident. It is important for healthcare organizations to ensure that pharmacy professionals are acknowledged and able to receive appropriate support in order to strive for a patient safety culture and a safe and effective healthcare system.

FINAL REMARKS

The term “second victim” was first introduced in the literature in 2000 to remind us that healthcare professionals involved in a patient safety event should not be forgotten, as they also need emotional and organizational support throughout the recovery process (Figure 2). However, recently there has been controversial discussion in the literature regarding the term “second victim”.10 Nevertheless, it is more important for us, as healthcare professionals, to:

- Acknowledge the fact that preventable medication harm is often due to both system factors and human factors;

- Openly discuss and learn from our errors; and

- Engage with patients, families, our peers, and healthcare organizations to work towards a safer healthcare system.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Lindsay Yoo, Dr. Mengdi Fei, and Ms. Jemima Selorio for their previous research and written work on this topic during their tenure at ISMP Canada. Dr. Yoo was a Medication Safety Analyst at ISMP Canada. Dr. Fei and Ms. Selorio completed a PharmD rotation at ISMP Canada in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Promoting a safety culture a fundamental component of the AIMS Program: The College

The promotion of a safety culture is an increasingly important aspect of quality improvement and patient safety in every part of our health system, including pharmacy. In a safety culture, which some organizations call a just culture, the focus is not on assigning blame, but on openly reviewing and discussing incidents and near misses within the team to understand why they happened, develop processes and take steps to prevent them from recurring and sharing those learnings with others.

Consistency in this approach is extremely important as it helps organizations and the people who are ultimately the heart of our health system – healthcare professionals – monitor and make improvements so that they know they’re having an impact on quality and patient safety. These are the principles of a safety culture, which is a fundamental component of the Assurance and Improvement in Medication Safety (AIMS) Program currently rolling out to community pharmacies across the province.

The Standards of Operations and supplemental Standard of Practice provide information for pharmacy staff and Designated Managers regarding their roles in promoting a safety culture in pharmacy along with the four core components of the AIMS Program. For more information, please visit the AIMS Program section on our website.

REFERENCES

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320 (7237):726-7.

- ISMP Canada. The Second Victim: Sharing the Journey toward Healing. ISMP Canada Safety Bulletin 2017 Oct;17(9):1-6. Available from: https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/safetyBulletins/2017/ISMPCSB2017-10-SecondVictim.pdf

- Edrees HH, Paine LA, Feroli ER, Wu AW. Health care workers as second victims of medical errors. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2011 Apr;121(4):101-8.

- Scott SD. The second victim phenomenon: a harsh reality of health care professions. Perspectives on Safety 2011 May. Available from: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspectives/perspective/102

- Burlison JD, Quillivan RR, Scott SD, Johnson S, Hoffman JM. The Effects of the Second Victim Phenomenon on Work-Related Outcomes: Connecting Self-Reported Caregiver Distress to Turnover Intentions and Absenteeism. Journal of Patient Safety 2016 Nov. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5413437/pdf/nihms-788857.pdf

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. BMJ Quality & Safety 2009 Oct 1;18(5):325-30.

- Harrison R, Lawton R, Perlo J, Gardner P, Armitage G, Shapiro J. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: a cross-country exploration. Journal of Patient Safety 2015 Mar;11(1):28-35.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Hahn-Cover K, Epperly KM, Phillips EC, Hall LW. Caring for our own: deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 2010 May 1;36(5):233-40.

- Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open 2016 Sep 1;6(9):e011708.

- Clarkson MD, Haskell H, Hemmelgarn C, Skolnik PJ. Abandon the term “second victim”: An appeal from families and patients harmed by medical errors. BMJ 2019;364:l1233.